Riverside 's Chinatowns

Riverside had two Chinatowns, and both are now gone. Thanks to local interest, their history, and the early history of Chinese in Riverside, has been very well documented.

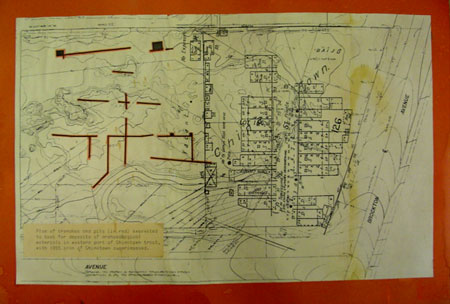

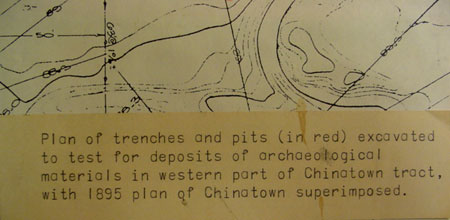

Archaeological work has provided a rich picture of Riverside 's Chinatown from the 1870s to the 1920s.

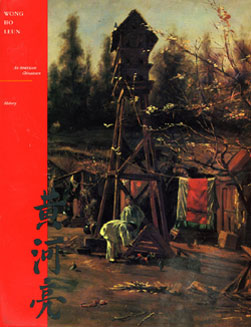

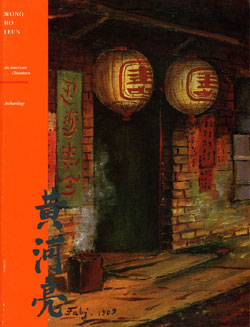

The two-volume monograph Wong Ho Leun: An American Chinatown (edited and published by The Great Basin Foundation, San Diego, 1987) is an extraordinarily detailed study of the archaeological excavation as well as a series of essays providing historical background on the Chinese in Riverside. It is out of print but widely available at local libraries, and we refer you to this book for much more information, including historical photographs, demographic statistics, firsthand accounts of Chinese laborers in early 20th century Riverside, and more.

Some immigrant Chinese settled in Riverside in the late 19th century, but many more came to work in the citrus groves that were the economic powerhouse of Riverside 's economy. At certain times of year, as many as 3,000 Chinese laborers lived here while they picked and packed fruit for wages. Many lived in temporary housing in or near the groves.

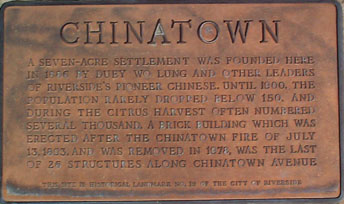

The first Chinatown in Riverside was in the downtown area, centered on Ninth Street. It included laundries, small restaurants, and more. A fire destroyed most of its structures and led to the establishment of a second Chinatown in 1885 in the Tequesquite Arroyo, in the shadow of Mt. Rubidoux on the outskirts of the city. This small community had as many as four hundred Chinese residents at some points. Many of them were from Gom-Benn, a village in the Toishan region of southern China; many had the family name Wong. Chinatown was sometime referred to as "Little Gom-Benn."

Another fire destroyed this Chinatown in 1893 but it was again rebuilt, featuring brick and wooden buildings, including a small temple. It included shops, a butcher, laundries, and residences, and it provided a number of services for migrant Chinese laborers. By the 1930s, it was in decline due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and dwindling numbers of Chinese in the area.

The last resident of Chinatown was George Wong, whose birth name Wong Ho Leun is the title of the publication noted above.

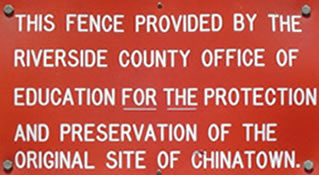

The Chinatown site is marked but closed to the public: it is an empty, overgrown field surrounded by a chain link fence.

A historical marker at the corner of Tequesquite and Palm Avenues commemorates this vanished community.

|

|

|

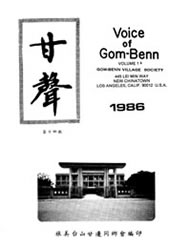

This newsletter is one way that members of the Gom-Benn Village Society continue to stay in touch with one another.

The community may be gone, but its people aren't. In the early to mid 20th century, many members of Riverside's Chinese resettled in other parts of Southern California. They formed the Gom-Benn Village Society, and their descendents still meet for a big annual dinner in Los Angeles.

The Chinese Pavilion in downtown Riverside on Mission Inn Avenue at Orange Street is a vivid memorial to the many Chinese who once lived here.