Interview with Alice Kanda

Held on August 18, 1999 at her home in Burbank, California. Present: Deborah Wong (interviewer), Alice Kanda, and her husband John Kanda. Total time: approx. 2 hours. Transcribed by Deborah Wong.

Alica Kanda, born Sumie Gotori in 1923, lived in Riverside from 1923-1942 was interned at Poston from 1942-45, and then returned to Riverside , living here from 1945-48 and then moving to Los Angeles . She has lived in the greater Los Angeles area ever since. Her memories are particularly interesting because she grew up in the Mexican/Mexican American neighborhood of Casablanca and thus had a lot of contact with non-Japanese Americans. Her story also hints at the social stratification of the Japanese American community in Riverside : it is clear that the Gotori family was seen as more working class than some of the other families. Mrs. Kanda's sister, Yo Clark, had an antique store called Clark 's Gallery in Riverside for many years, and their parents lived in Riverside until their deaths in 1965 and 1974, so Mrs. Kanda has continued to visit until recently. The antique store was finally closed and sold in 2000.

A few other Japanese American families lived in Casablanca during this period, though Alice doesn't mention them. The Nishimoto family lived off Madison Street , at the end of Frieda Drive , where the new branch of the Riverside public library is located, and Alice remembers that they had a house and a small store as well as big farm where they raised blackberries and asparagus. The Nishimotos did not return to Riverside after internment. The Takeda family also lived nearby and had a small grocery store.

Alice remembers going to Olivewood Memorial Park with her mother in order to visit the grave of an older sibling who died as a child:

Photograph of Kanichi Gotori's headstone.

After checking the transcript of this interview, Mrs. Kanda wrote to me:

Almost daily our folks would remind us the importance of being good citizens., especially since we were of Japanese ancestry, "a race not liked." There are two Japanese expressions my father taught us: tasukeru, which means to help or rescue, and the other, gaman, which means to endure. Learned in camp, these two phrases were instilled in many families' children

In 2000, I asked her to show me the house where she grew up:

Alice Kanda outside her childhood home in the Casablanca neighborhood of Riverside in 1999.

Deborah Wong: It's Wednesday, August 18 th , I think.

Alice Kanda: Yes.

Deborah Wong: And I'm in Burbank , in the home of Alice and John Kanda.

Alice Kanda: You might say 'Sue', too-nobody will know me as ' Alice '.

Deborah Wong: Oh really? So you go by Sue?

Alice Kanda: Well, see, my Japanese name is Sumie, and when I went to school, my third grade teacher couldn't pronounce it, so they rolled on the floor-you know how little kids do. No, this was in the first grade. So finally she said, "You're going to be Alice ," and since then, I've been Alice .

Deborah Wong: Oh for Pete's sake.

Alice Kanda: So it is not my legal name.

Deborah Wong: I guess it was a different time. I guess that was a time when teachers felt free to rename their students. Let's just proceed like this is a conversation. When I do these interviews with a tape and everything, it doesn't need to be formal. Probably the only people who will listen to this again will be me and a student who will transcribe the thing onto computer. What we do is to get it all down, and once we have it all transcribed, I'll send a copy to you so you can look it over, and it may well prompt other memories or corrections or whatever else. So that's why I tape it. Just to get it all down. So could we start at the beginning? If you don't mind my asking, where were you born and what year was it?

Alice Kanda: I was born in Riverside , but it was called Casablanca . Oh no, wait a minute-I wasn't born there! [ laughter ] I was born in a place called Prenda. [ to her husband John ] How many miles is it from there to the packing house in that area? You know, where the orange packing house was?

John Kanda: Oh, the orange packing house?

Alice Kanda: Uh-huh. That used to be called Prenda. [Editor's note: Prenda was at Victoria and Madison, on Dufferin.]

John Kanda: Oh, it did?

Alice Kanda: Uh-huh. Yeah. Brenda. It's no longer-I was born in 1923, so, yeah. It must be about five miles from Casablanca . You know Casablanca ?

Deborah Wong: Sure do.

Alice Kanda: My folks had a mom and pop store.

Deborah Wong: Oh yeah?

Alice Kanda: Yeah, they bought a piece of property there, and they built the store. I can remember them digging the cellar. That I can remember from when they were building it.

Deborah Wong: Wow. So they really built it.

Alice Kanda: They built it-yeah. It's a shop but they built it-had it built.

Deborah Wong: What was the location of that store?

Alice Kanda: Oh yeah, it's on Madison close to-what's that cross street? It's not Frieda. Is it Frieda?

John Kanda: I think it is Frieda, but Lincoln is one block south.

Alice Kanda: It's between Lincoln and Frieda, but it's closer to Frieda, on Madison .

John Kanda: On Madison . Right on the corner.

Alice Kanda: Yeah. And they've painted the house. Is it yellow now? I think it's yellow, and they have a new structure right next to it.

Deborah Wong: Oh, so it's still there?

Alice Kanda: It's still there, uh-huh. Right.

Deborah Wong: OK. That's not always true in Riverside -a lot of stuff has vanished.

Alice Kanda: Right. And we went to school in Casablanca , which is how many blocks away. Maybe not even two blocks away.

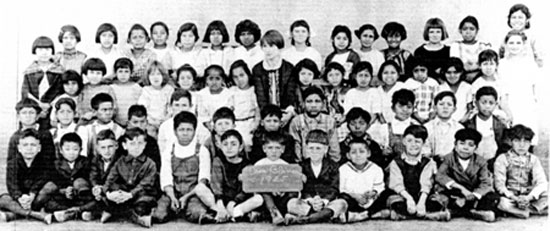

Photograph of the students at the Casablanca school in 1925. The Asian boy (front row, second from the left) is probably Massa Hatta. (Courtesy of the Riverside Metropolitan Museum.)

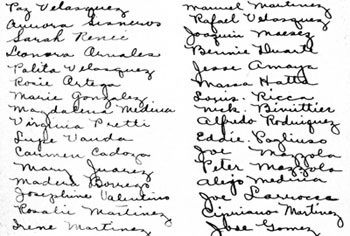

List of students' names on the back of the photograph.

Deborah Wong: That was your neighborhood.

Alice Kanda: Right. My mother learned to speak Spanish before she even learned to speak English, I think, because of her clientele.

Deborah Wong: That makes sense. Of course that neighborhood is almost entirely Mexican and Mexican American now.

Alice Kanda: Right.

John Kanda: It was then, too.

Alice Kanda: But after the war, the blacks were there-quite a few blacks came in. I don't think they stayed too long.

Deborah Wong: No, they're mostly on the Eastside now, I would say.

Alice Kanda: Yeah. I can remember my folks after the war, they opened the store again, but they had to let so many kids in and then lock the door, because they couldn't control the kids and keep their eyes on them. [ laughed ] Because they were pilfering, you know! And so they did that for awhile, but finally it got to be too much for them and so they closed it, but they had it for years and years-as long as I can remember.

Deborah Wong: Was it a general store?

Alice Kanda: Yeah, it was just groceries, and she carried some lunch meat and a little produce, and lots of candy, I remember that! And a gas pump. Was it one gas pump, or two?

John Kanda: You had two gas pumps.

Alice Kanda: Two gas pumps. [ laughed ] See, John was out there a lot, so he remembers.

Deborah Wong [ to John ]: Were you born in Riverside as well?

John Kanda: No-I was born in Los Angeles .

Deborah Wong: Oh, in LA-all right.

John Kanda: I didn't know anything about Riverside .

Alice Kanda: Until we met, yeah.

Deborah Wong: OK-[ to John ] I'm going to get you into the picture as I go along here. You're both Nisei, I think.

Alice Kanda: Yeah.

Deborah Wong: Where did your parents come from in Japan ?

Alice Kanda: They came from a place called Nagoya .

Deborah Wong: Do you know what year they emigrated?

Alice Kanda: Gee, I don't know what year, but I know my father was sixteen or seventeen. And he came illegally, because he came through Mexico .

Deborah Wong: Really? That's unusual.

Alice Kanda: Uh-huh. So when the war broke out, he had nothing to show that he was a resident here except for some old postcards. I remember my mother telling me that, and I had that postcard, but I don't know what happened to one of them. It gave the date that the postcard was written to him here, so that was enough for them, apparently. But he was picked up by the FBI after the war broke out, like so many of the Isseis. You know, they rounded them all up and then they were in the city jail for a few days and then they were shipped, and we didn't know where he was for over a year.

Deborah Wong: A year.

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm. And in the meantime we were evacuated, and we were in Poston , Arizona , which is near Parker Dam.

Deborah Wong: Right-just across the border.

Alice Kanda: Right.

Deborah Wong: Do I hear your rice pot rattling?

Alice Kanda [ to John ]: You're supposed to be-!

John Kanda: I haven't got my hearing aid on!

Alice Kanda: [ laughing ] You're supposed to be watching the rice!

Deborah Wong: [ laughing ] I think your rice is boiling!

Alice Kanda: You can hear it, huh? [ laughing ] Oh, goodness. The way they rounded these men up. They went to the Japanese homes at one time-I mean, so there was no calling up, so neighbors could say, "They're here," or whatever. That surprised me-that everyone was rounded up at the same time. That's what the FBI told me, anyway. I said in Japanese to my mother, "Should I go tell So-and-so, who's a neighbor?" And he says, "You don't need to, because everyone's being picked up at the same time." He understood what I said in Japanese!

Deborah Wong: Wow. Let's back up a bit. It sounds like your father was probably born in 190-something.

Alice Kanda: Let's see now. He died when he was 78, in 1965. [Her father was therefore born in 1887 and emigrated in 1903 or 1904.]

Deborah Wong: I guess your mother didn't come over at the same time as your father?

Alice Kanda: No. At that time, you know, there were picture brides. So my mom came over I think when she was 18 or so.

Deborah Wong: Was she also from Nagoya ?

Alice Kanda: Yes. She's from Nagoya also. My dad had a high school education. He got it at night-he went to night school.

Deborah Wong: In the U.S. ?

Alice Kanda: Yes, in the U.S.

Deborah Wong: Wow. Good for him. Did the family support itself through the general store. Or did you do other things as well?

Alice Kanda: When we got old enough to take care of the store, my mother worked out, and she packed oranges. And then my father always worked out-he tended the orange groves for different people.

Deborah Wong: Not just for one company?

Alice Kanda: Oh no, he worked for about three different people. And he used a smudge too, you know-when it got cold, to keep the trees from freezing, they put these pots up-I don't know if you've ever seen them-you don't have them anymore, they have these windmill things now. That's the way he used to keep the orange groves from freezing. The doctors said that's probably what killed him, because he got aplastic anemia and it went into leukemia.

Deborah Wong: Really? And they think that was related to working in the citrus groves?

Alice Kanda: Right. That's what the doctor felt. At first, when they found he was anemic, they asked if he was a painter, and I said that no, he worked in the orange groves, and he said, insecticides and so on. So anyway. He was young compared to some of these Isseis that are now passing away. You see so many of them in their nineties.

Deborah Wong: So he was in his seventies when he passed?

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm. My mother was 83 when she died, and that was in 1975, I think. Or 74-she died in 1974. [Her mother was therefore born in 1892.]

Deborah Wong: So there was you, and your sister. Did you have other siblings, besides the sister who owned the antique store?

Alice Kanda: I have, still remaining, four sisters and four brothers.

Deborah Wong: Wow! [ everyone laughs ]

Alice Kanda: Oh, three sisters-I was counting myself.

Deborah Wong: That's a lot of people!

Alice Kanda: Oh yeah. I have one sister-what part of Alabama did she move to? Piedmont ! Piedmont , Alabama . She lived in Atlanta for a number of years, but because her husband's mother got ill, they had to move closer to her. And then I have a brother who is retired from the Air Force, and he's in Pearl City , Hawaii . And then I have another brother in Aurora , Colorado . That's it, for those outside of California .

John Kanda: The rest are here.

Deborah Wong: Where in California ?

Alice Kanda: I have one sister in the Valley, and I have another sister that lives in South Pasadena , and a brother in Monterey Park , and one in Simi Valley .

Deborah Wong: So half of you are still here, and the rest are scattered.

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm, right.

Deborah Wong: No one's left in Riverside , then?

Alice Kanda: No, Yo was the only one, and she stayed there because of the business, I'm sure, and then because of my folks, because she looked after them.

Deborah Wong: Where did your parents live, until the 70s?

Alice Kanda: In Casablanca-they stayed there. After the war, we came back to the same location, cause we had rented the store. The store was attached to the house, and so we rented the whole thing out, and came back to that same house.

Deborah Wong: You managed to hold onto it?

Alice Kanda: Well, we had it rented to a Mexican family. We had shut the basement down-nailed it down-but when we got back, our furniture was all gone.

Deborah Wong: So you had the building.

Alice Kanda: Yeah. We were lucky we had a place to-that we had a roof over our heads when we came back!

Deborah Wong: That's more than some people had.

Alice Kanda: Yeah.

Deborah Wong: But still, that must have been hard.

Alice Kanda: It was. In fact, I was telling some people that were here Sunday, for years I couldn't talk about evacuation or the camp. You know, I'd get emotional about it. But I'm better now. [laughed] Better than I was. Yeah.

Deborah Wong: I know that for a lot of Niseis, it's a very difficult topic. It happened when you were young people, at a very formative point in your lives.

Alice Kanda: Right.

Deborah Wong: There were eight kids, right?

Alice Kanda: Nine kids-there were nine of us.

Deborah Wong: Plus two parents. So all eleven of you went off to Poston.

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm, though my dad wasn't with us. And my two older sisters were married, so they were out of the house, so it was up to me to pack things and to get rid of the merchandise. Mom had to have an income to feed us until we left for camp, so she kept packing oranges until almost a few days before we left, I think.

Deborah Wong: So you were the next oldest, and you had to-

Alice Kanda: Yeah, there were two older than me, but they were gone from the house, so.

Deborah Wong: I see. And you were. nineteen.

Alice Kanda: I was nineteen-eighteen.

John Kanda: Seventeen.

Alice Kanda: Seventeen?

John Kanda: And I was eighteen.

Alice Kanda: OK. And I was, like, all these good-for-nothing kids! They can't even, you know, carry anything, because they were all young. Yeah, I remember that.

Deborah Wong: It was a big responsibility.

Alice Kanda: Yeah.

Deborah Wong: So which schools did you go to in Riverside ?

Alice Kanda: First I went to Casablanca for my elementary, and the middle school was in Arlington - Chemawa Junior High School . And then I went to Poly High.

Deborah Wong: Was that the only high school in the area at that time?

Alice Kanda: I think it was. And I didn't graduate because the war came, and they sent me my diploma.

Deborah Wong: In the mail?

Alice Kanda: In the mail.

John Kanda: It wasn't in that same location, though.

Alice Kanda: No, it wasn't. Poly High was where that JC is now-where that hole is.

Deborah Wong: Oh yeah-it's like a sports field, I think.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, right. Because that's where the football field was, that hole.

Deborah Wong: Oh, so it was downtown at that point? I had no idea. So that's where you went. You must have been in your senior year when you were evacuated. I just interviewed someone two days, Michiko Yoshimura-

Alice Kanda: Oh, yeah.

Deborah Wong: Oh, you do know her!

Alice Kanda: My brother is married to her sister-my youngest brother. Oh yeah, we've known each other for years. We go there for New Year's and have the best New Year's dinner!

Deborah Wong: I should have known!

Alice Kanda: Yeah but I never did know too many of the Japanese people before the war because we lived near the tracks, so to speak [ i.e., in a Mexican neighborhood ], so we were like outcasts, you know. [ laughed ]

Deborah Wong: She did mention some other Japanese American families that lived in the Casablanca neighborhood, and I'm wondering if you knew any of them. The Takedas?

Alice Kanda: The Takedas? Yes, they were our neighbors, yeah. But I don't know where they are now.

Deborah Wong: I don't know either. I'd be interested in tracking down some of these folks.

Alice Kanda: At one time, Sho-he's a dentist-and he may be listed in the Riverside telephone directory. He may still be practicing in Riverside , I'm not too sure. And then if you get in touch with him, he could tell you where his sister is. At one time she was in San Diego , but she's been married, and so on.

Deborah Wong: It seems like a lot of folks have moved away.

Alice Kanda: Oh yeah. Very few have stayed. Now see, Michiko came to live there after the war. She was not a Riversider. I bet she told you that.

Deborah Wong: Yeah, it was 1950-something. 1954-something like that. She also mentioned-oh, maybe this is you!-the Gotoris on Madison .

Alice Kanda: Yeah, I'm a Gotori. Is the rice OK, John?

John Kanda: I just turned it off completely. I turned it down low for about eight minutes.

Alice Kanda: Oh, you're supposed to let it cook about fifteen minutes. I do. Anyway.

John Kanda: I can go turn it back on.

Alice Kanda: Very low! [ laughs ]

Deborah Wong: What about the Isedas? Mr. Iseda was a community leader of some sort.

Alice Kanda: Oh yeah. He wanted to be.

Deborah Wong: He wanted to be?

Alice Kanda: I should be quiet. [ We both laugh ] Of course, he's gone, but I don't know where the kids are.

Deborah Wong: She didn't know either. Mrs. Taneguchi?

Alice Kanda: The Taneguchis are still there. They're on Lincoln . Of course, the only one that's there now is Yoshio, and he was older than me, and his wife and family. But they are on Lincoln .

Deborah Wong: And the Yoshidas.

Alice Kanda: Oh, they're gone, but I don't know where.

Deborah Wong: Oh, OK. Well, those are the ones she mentioned for Casablanca . So describe the neighborhood when you were a kid.

Alice Kanda: The neighborhood? Well, I didn't know I was in a depressed area until I grew up! [laughed] And it was a depressed area-it was a ghetto, because it was all predominantly Mexicans, you know, and they were orange-pickers. The majority of them picked oranges or packed oranges. That's the kind of people my mother catered to in the business.

John Kanda: And the gypsies came through every once in awhile.

Alice Kanda: Oh yes, would come around. Gypsies, yes. One time, I saw the gypsies out of the school window. I was in the third grade, and I ran home to tell my mother that the gypsies were in town so close the store. Well, when I got there, my mother was bound-they had bound her up, had taken the money out of the cash register.

Deborah Wong: Really?

Alice Kanda: I remember that, because I told the teacher, "I gotta go home 'cause I gotta tell my mom the gypsies are in town and to close up the store," you know.

Deborah Wong: This is news to me. I never heard of gypsies in California . They were folks who would come into town-?

Alice Kanda: Yeah. They didn't live there, they'd come from somewhere, I don't know where.

Deborah Wong: And they robbed your store!

Alice Kanda: Yeah. They robbed my mother. I remember that. So after that, when I was in grade school, if I saw them, I would run and-'cause I was so close to home-school was only a couple of blocks, short blocks, so I used to run home.

Deborah Wong: So you could see them coming up the street.

Alice Kanda: Yeah! They would be walking, most of the time. That's how I'd see them, you know.

Deborah Wong: What kids did you play with? Were the mostly Japanese American, or were they Mexican, or-

Alice Kanda: They were mostly Mexicans, though I don't remember having too much time to play, because a I said, I was the older one, so when I was old enough, I'd open the store and work in the store until my mother got home and so on.

Deborah Wong: So playing was not a large part of your childhood.

Alice Kanda: No, no, no. In fact, I never even went to a football game. I had to get home. Or any game. I can't remember going to a game. But I do remember, in the sixth grade, when we graduated, they took us to Fairmount Park and they gave us some hot food, and I didn't know what it was until three or four years later, that that was stew. [ laughed ] 'Cause there were hunks of vegetables and meat, and because when my mother made stew it was watery. So that was stew.

Deborah Wong: Did you speak any Spanish as a kid?

Alice Kanda: A little. I took it in school, but I can speak only a little now. But we went to Japanese school on Sundays for years . I hated it but we went to Japanese school. We came home and spoke English. I used to say to my mother, "Why do you spend the money, we're so poor, and you're paying the school. The teacher-you're feeding him lunch and giving him gas." [ laughed ] My mother used to get so angry at me, but you know, I thought that money could go for something else.

Deborah Wong: I guess it was important to your parents.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, they wanted us to get some cultural background. But we spoke English at home.

Deborah Wong: What was your first language? Was it Japanese or English? What did you first speak at home?

Alice Kanda: Oh, English. My folks were speaking broken English.

Deborah Wong: I assume your parents spoke Japanese to each other.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, they'd speak Japanese most of the time. But as the younger kids started growing up, they'd speak broken English.

Deborah Wong: So it sounds like the Japanese teacher came to your house?

Alice Kanda: No. We went to a building, and we either walked or got a ride.

Deborah Wong: Where was that?

Alice Kanda: In Arlington . That's where it originated. And then they'd go to school in Casablanca on Lincoln Street , and that's where we went.

Deborah Wong: I would have thought it would be held in the Japanese Union Church that everybody always mentions.

Alice Kanda: I didn't ever know that they had a Union Church. [laughed] Until years later.

Deborah Wong: How many kids were taking Japanese classes with you?

Alice Kanda: Oh, I'd say about fifty. I remember when the teacher first came from Japan -of course you know we had orange groves, though most of them are gone now. They had these naval oranges and there were these signs saying that if you pick oranges, there's a fine. Of course they couldn't read English, but they saw these huge navel oranges and they ran in there and started picking them. [laughed] We kept telling them, "You can't do that! You're gonna get arrested!" They didn't hear us.

Deborah Wong: In Japanese school, was it just language that you learned?

Alice Kanda: No, we learned flower arrangement, we learned dancing, and music-singing. So once a year, we used to put on a program. If you were a speaker, you talked about a book you read or whatever.

Deborah Wong: What time of year was that show put on, usually?

Alice Kanda: I think it was in the summertime. They used to build a stage. In Beaumont , they used to have the cherry festival and we used to all participate. My dad and I used to dance together. We'd get our Japanese kimonos on. My folks tried to give us violin lessons and piano lessons.

Deborah Wong: That's part of being American, isn't it!

Alice Kanda: Yeah, right!

Deborah Wong: In Riverside, was there an Obon festival at all, in July?

Alice Kanda: No, we didn't have 'em. I don't remember having the Obon festival, although maybe that's what it was and I wasn't aware of it, but no.

Deborah Wong: There wasn't any Japanese Buddhist temple, was there?

Alice Kanda: In Riverside ? No. We didn't pray in school, no. The only time we did have services was when somebody passed away, that I can remember. And then as we got older, my folks used to go to LA. I remember driving them in-I drove them in, at fourteen! [ laughed ] Yeah. I got a ticket for driving without a license, on Victoria . It was my younger brother-he was younger, and he taught me how to drive, but when he saw this motorcycle policeman, he got frightened, so he said, "You drive, you drive," and so I drove, but I got off Victoria and I went into the orange groves. Well, the policeman followed us. [ laughed ] And he gave me a ticket, and my dad and I had to go to court. I was so nervous. You know, you go before the judge, and he said, "Do you plead guilty or not guilty?" I was stuttering! [ laughed ] And the policeman that arrested us was there, and he turned away because he was laughing. But the policeman said I drove like I knew what I was doing, so they should issue me a learner's permit. So I got my learner's permit and then I got a diver's license.

Deborah Wong: So why did he pull you over then, if you looked like you knew what you were doing?

Alice Kanda: Well, because, see, my brother was driving, and then-

John Kanda: They switched.

Alice Kanda: We switched, so he said, "Oh-these are two young kids." [ laughed ]

Deborah Wong: Well, that's one way to get a learner's permit! So when you drove your parents to LA, I assume you were taking them to Little Tokyo?

Alice Kanda: Yeah-to Little Tokyo, and to the Buddhist church.

Deborah Wong: So your family was Buddhist?

Alice Kanda: My mother and father were. We followed them until we got old enough to decide what we wanted to do with religion.

Deborah Wong: What direction did you choose when you were older?

Alice Kanda: Well, I went to a Lutheran church, and that was in Casablanca .

Deborah Wong: My general sense is that there were a bunch of Catholic churches there.

Alice Kanda: Yeah.

Deborah Wong: So if you don't mind my asking, how did the two of you find each other?

Alice Kanda: I came to LA in '48 and went to work for the phone company, and I was working for my room and board too, but I went to work for the phone company and there was a gal-she approached me-a Caucasian girl-and she said, "Would you like to meet a nice Japanese boy?" And I said, "Yeah, someday." And she said, "No, would you like to double-date?" And I said, "Yes, someday"! [ laughed ] After six months of saying, "Well, I have to go home to Riverside to see my parents." And I used to take the bus back and forth, on weekends.

Deborah Wong: I bet that would take awhile.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, it did, it took at least two hours or more, to take the bus from LA to Riverside . But anyway, after six months, I finally decided to go on a date, and that's how I met John. We'll be married fifty years next June.

Deborah Wong: Wow!

Alice Kanda: [ laughed ] We were kids when we got married! And John was in business. He had a garage and a service station, and he couldn't pick me up a number of times and he had-what was his name?

John Kanda: Ike.

Alice Kanda: Ike-a black man. And I was working for the president of the Broadway department store, but at that time it was called Carter's or something-I was working for him. I was the maid that opened the door and so on. And they were having a party that night and I was going out with John later on, and I opened the door and here was this black man, and he says, "I'm here to pick up Alice ." And Mrs. Carter says, "Have him go to the back," you know. [ laughed ] So he came to the back. [ laughed ] It was a shocker to see this black man come to pick me up, and he said. "John asked me to come and pick you up-he's busy at the service station right now." So that's how we met.

Deborah Wong: [ to John ] Where was your service station?

John Kanda: It was right down on La Brea on Adam Boulevard -on La Brea in Los Angeles , Westside area.

Deborah Wong: How long did you work there?

John Kanda: Two years, three years. It was a garage as well as a service station, so we did a lot of car repair.

Alice Kanda: He would work until 2, 3 o'clock in the morning, or sometimes later, and this happened quite often, even after we got married, too. He worked hard. Worked seven days a week.

John Kanda: In those days, they didn't have credit cards, so if they had to have credit, you were the ones stuck with it.

Deborah Wong: But it sounds like you also went out to Riverside .

John Kanda: No. We just met on this blind date. Tommy's boyfriend was somebody I knew from way back in 1935, I guess.

Alice Kanda: He was a White, Caucasian-

John Kanda: -a friend of mine.

Alice Kanda: And it was his girlfriend that approached me about John, 'cause she worked at the phone company too. In fact, last Sunday we had some people here. I got TB when I was in camp. I worked as nurses' aid and took care of TB patients, so I got TB.

John Kanda: The thing is, they didn't tell her they were TB patients.

Alice Kanda: They wouldn't tell us hardly anything. We'd have to look in the chart. In fact, I took care of a woman who had syphilis-she had these sores in her head-and I was suspicious, so when they were all gone, I read her chart and I thought, "Yeah, that's what I thought." But I was very careful. But during those times, the Japanese didn't want people to know they had TB. They were ashamed. I don't know what it was.

Deborah Wong: It's really infectious, isn't it?

Alice Kanda: Yes, it was, very.

John Kanda: They would kind of ostracize you-

Alice Kanda: -if you had TB or diabetes. But anyway, I got TB. I wasn't the only nurses' aid that got it, there were a few others. They sent us to Phoenix to an Indian sanitarium.

Deborah Wong: Really!

Alice Kanda: Yes. And Betsy went first, I think, and we came later, but her husband was able to leave the camp and live in Phoenix so that he could be close to her. Well, every Sunday, this man used to make us rice balls and chicken and teriyaki and some pickles, you know, and bring lunch to us. And we'd look forward to it, you know, 'cause that was the only ethnic food we got. So he did that for almost two years. He finally moved from Phoenix to Gardena , recently. He's 87 years old. So we had him here for dinner Sunday with a few of the girls that he knew, and it was quite an emotional thing, for me especially 'cause I had known him the longest, you know. Betsy passed away about sixteen years ago, and he took care of her for ten and a half years-she got cancer. And then he remarried. But I was so glad he was here. Those times at the sanitarium. Being away from your family was rough. It was rough for me 'cause I was the oldest-'cause my father wasn't there, and I kept wondering, "What's happening to the family?" and so on and so forth.

Deborah Wong: So how long were you at Poston, then, before you went to Phoenix ?

Alice Kanda: Let's see. We didn't come home till '45 and we went there in '42. When the war started I was in high school, at Poly, and the principal made this announcement over the loudspeaker, that they should treat us like they'd been treating us, that we're not the enemy, you know, we're American citizens.

Deborah Wong: Your principal did that?

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm. He made an announcement, yeah. Then when I went to work for the phone company, I was the first Japanese girl to be hired in that department, so then they also made an announcement. [ laughed ] And there was this gal-she was huge, both ways-tall and I'll never forget it, she came walking toward me and she said all these bad words in Japanese, and you know, coming from the country, I was just like this [ open-mouthed ], you know, looking at her. [ laughed ] And then she laughed, you know. I thought, wow. Then later on, she said she'd been raised by Japanese families nearby, so she knew good Japanese food and so on and so forth.

Deborah Wong: So Pearl Harbor was in December, and as I remember, it was in May of '42 that the Japanese American families in Riverside were evacuated.

Alice Kanda: Yeah. I thought we went in April, but it could have been in May.

Deborah Wong: So you were in Riverside for a good four or five months from the beginning of the American involvement in the war to the time you were all carted out of there. How was it, to be in school at that point, despite what your principal said?

Alice Kanda: How was it? It was kind of scary. I used to come home on weekends and I tried to leave there when it was light. My mother closed the store because she was afraid, although the Mexicans didn't harm us or anything. But she thought it'd be safer if we closed the store. So she closed it and was working at the packing house like I said until a few days before we left.

Deborah Wong: So she was supporting the whole family.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, she was. Like I say, I was the oldest at home, and all these little kids. The ninth grade summer, I went to work at Lake Arrowhead . I had two jobs. It was the same family. I took tickets at the theater and then I baby-sat-took care of the kids. So this woman came to see me after the war, and while she was talking to me, I passed out. I didn't know what had happened. I guess the responsibility got too much for me, with everything, and then when she came to offer help, I guess I was so overwhelmed that someone would come and see if there was anything she could do for us.

Deborah Wong: A good person.

Alice Kanda: Right. In fact, I went to see her, oh, several years ago. I found out where she was and I was able to thank her. Mexicans didn't bother us. No. I don't even remember any bad incidents-nobody throwing rocks or. Oh, they called us names. I mean, you know: Jap, you know. I don't think they really knew what they were saying. They were kids, mostly-no adults.

Deborah Wong: Was that at school?

Alice Kanda: Yeah, at school. But then most of us quit school early after the war.

Deborah Wong: So during those winter and spring months of '42, nothing happened to your family but it was a tense time, an anxious time.

Alice Kanda: Well, like I say, my dad left early, before we were evacuated.

Deborah Wong: Before all that, as a kid, did you experience any racism or discrimination as a Japanese American? Any incidents that you remember?

Alice Kanda: No, I really can't remember anything besides kids calling us Japs. But we used to call them "you dirty old Mexicans," too, so.! [ laughed ] Or say it in Spanish! I think the people in Casablanca really respected my mother because we used to go shopping and I used to get so embarrassed because they would call out, "Hello mama, come sta, mama?" [ laughed ] I would try to hide behind her. And even on the other side of Main Street , they would yell at my mother, say, " Come sta, mama!"

Deborah Wong: I guess they liked her. She was a figure in the community.

Alice Kanda: The older generation called her "mama." And on weekends, when my mother had the store closed on Sundays, they'd come knocking on the back door if they needed milk or something. My mother would open it and give them the milk or whatever. Even after the war, she'd be working in the garden and my dad would be gone and they'd go in the store and get bread or something and they'd tell Mama, "I got a loaf of bread" in Spanish, and "I put the money on the cash register." During those days you could trust most everyone.

Deborah Wong: Did your parents manage to buy the house and the land, then?

Alice Kanda: Yeah. They put it in our name. They put it in my older sisters' and my name.

Deborah Wong: Like so many Issei had to do because of the Alien Land Law.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, right, right. But if they really wanted to get technical about it. we were minors.

Deborah Wong: Did you know the Haradas?

Alice Kanda: I knew of them. I know Sumi. She's somewhere in Culver City in a retirement home.

Deborah Wong: So I'm told. Of course it's their house that gave that law a test.

Alice Kanda: It's now a historical landmark on Lemon Street .

[We talk about the Harada house and the legal case for a few minutes.]

Alice Kanda: We couldn't buy a house after the war. John had been in the service.

John Kanda: I was in the 442 nd . The 100 th battalion.

Deborah Wong: Really?!

John Kanda: But then I couldn't buy a house.

Alice Kanda: His brother died in Italy .

John Kanda: He was in the 442.

Deborah Wong: Both of you. Oh my.

John Kanda: Actually, they did us a favor, because the neighborhood we were going to buy in has gone down, and we bought another place, a new place, and it added income and helped us. It was a better house. But the neighborhood did go down there, too.

Alice Kanda: The reason we were going to move out there.

John Kanda: My best friend [and best man] was a Caucasian. He bought a house in the next block-

Alice Kanda: Across the street.

John Kanda: He said, "Come on out here-they've got some pretty nice little houses out here." I went out, and. no deal. They wouldn't really say why, because my credit passed approval-everything was all OK. But they just said, "We can't accept it."

Deborah Wong: I see.

Alice Kanda: That was a blow. That's the time that I really felt discrimination. Until then, it was there, but I never let it upset me as much as that time.

Deborah Wong: But that got to you.

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm. That really got to me. And then we went to a lawyer, remember? That Japanese lawyer down on Eastside? He wasn't interested. I guess he looked at us and thought we didn't have any money!

Deborah Wong: What year was that, when you were trying to buy the house?

Alice Kanda: Let's see, we got married in '48-I mean, '50! So it must have been around '52.

John Kanda: Yeah. Even if you had a uniform on during the war, you'd go to places and see signs saying "No Japs allowed." Even if you had a uniform on.

Deborah Wong: [ to John ] Were you in the camps as well?

John Kanda: Yeah, I was in Grenada . Well, I went to Santa Anita first-the place for the racehorses. I went to Santa Anita and then they asked for volunteers to work on a farm, so I went to Idaho and worked on a farm there. I guess our group was kind of a bunch of rabble-rousers. We stood up for our rights too much, I guess, and they asked us, "Would you like to go back to Santa Anita and help your parents move to Grenada ?" We said, "OK."

Alice Kanda: Yeah, but tell her about the time you were hired by a minister.

John Kanda: That was in Idaho . He invited us in to hear his sermon. He said, "Come on in! Come on in! Glad to have you boys in!" So we sat there for an hour listening to the sermon, and he was real cheerful. He said, "Come any time." The next day, we were working his farm-we didn't know it was going to be his farm-and we sat down for a break. And when we sat down for a break-you know, we were just talking-and he came along. "What're you guys doing?" I said, "We're taking a break. We're kinda tired from that last run, weeding in that grove." And he says, "You know, you boys should be working. After all, the people here don't like you, and they don't want you here. So if you don't keep on working, they're not gonna let you stay around here."

Alice Kanda: Didn't he call you 'Japs', too? No-did he say, "They don't like Japs"?

John Kanda: "They don't like Japs." And so we looked up at him, and-"Good-by!" Took off!

Deborah Wong: Really? You left the farm?

John Kanda: Yeah. We left that farm. See, we were hired out to work at different farms all the time, so it wasn't just his farm. So we stayed there for another couple of months, working around there, and then we all drifted off.

Deborah Wong: At what point did you enlist?

John Kanda: Oh, I was working in Denver as a mechanic.

Deborah Wong: Oh gosh, you got around

John Kanda: And then ended up. Well, the draft caught up with me there.

Deborah Wong: Wow. So you went from LA to Idaho to Colorado to. Where did you fight?

John Kanda: In Italy . I just caught the tail end of it. I was lucky. My brother was in there from before the war. He was in Fort MacArthur , and when the war broke out, they had to restrict him to barracks because they didn't know what to do with him.

Alice Kanda: When we were in Venice , we saw this well-groomed man, beautifully dressed, with this beautiful poodle coming over, and when he came over, he said, " Japonez ? Japonez?" And John said, "No, we're American." Ad he says, "Americano? No! Americano? No! Americano no good!" And he pulled the dog-[ laughed ]

John Kanda: He pulled the dog back away from us! [ laughed ]

Alice Kanda: And then we were in Rome and had bought a gelato, and the man asked John if he was Japanese, and John says, "No, I'm Americano"-you know, he just comes out and says, "I'm American," and he says, "Americano? No Americano!" [ laughed ] I didn't feel any prejudice for many, many years before I went there!

Deborah Wong: I take it this because of NATO and so forth?

John Kanda: Yeah, because the U.S. was doing that bombing and bombing runs, and your mother had that sign, "STOP THE WAR"! [ laughed ] One of the fishermen, in his nets, dragged up one of those bombs, so that's why they went on strike, and the Italians were really kind of up in arms about it. And that's when this happened. "Americano! No!" [ laughed ]

Alice Kanda: You see, Deborah, there were a lot of Japanese from Japan touring too, so that's why he-

John Kanda: So should have just said, "Yes, we are Japanese!" [ laughed ]

Alice Kanda: Did Fujimoto say-wasn't Charles that you interviewed?

Deborah Wong: George-it was George.

Alice Kanda: Oh, George. Oh, uh-huh. Charles was the younger one, I think. Did he feel a lot of prejudice?

Deborah Wong: I've only had one conversation with Mr. Fujimoto, and in his diaries, he's almost distanced from everything. So I don't know, yet. Certainly in the diary he talks about the atmosphere in Riverside at the time and it's clear that it was pretty tense for Japanese Americans, partly because nobody knew what was going to happen. George is going to come to Riverside in October and again in December, and at that point I hope to have some long interviews with him, in preparation for publishing his diaries.

Alice Kanda: Where is he now?

Deborah Wong: Way the heck up in Washington State . But his son is in Moreno Valley , and his sister Mable is still in Riverside , so I want to talk with her at some point.

Alice Kanda: I've seen Mable a few times because she's a friend of Michiko Yoshimura. Like I say, we didn't associate with too many-or rather, they didn't want to associate with us 'cause we lived near the railroad tracks, so that was all right. [ laughed ]

Deborah Wong: So there was a real sense of-I don't know what to call it-differences in social status within the Japanese American community?

Alice Kanda: Oh yeah, you know. Well, we lived in the Mexican town too, although they lived in the country, but they weren't in the Mexican town like we were.

Deborah Wong: How did you get that sense? How did you know , as you got older?

Alice Kanda: Well, when we went to school, they wouldn't. You know.

Deborah Wong: It was made clear to you.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, right. So that was OK with me. [ laughed ]

Deborah Wong: What's clear tome is that many of the Japanese Americans in town were farmers of one sort or another, many of them leasing land to do strawberries or chickens or whatever.

Alice Kanda: My folks had bought-I don't know how they did it, but they had bought two lots. And it was a corner lot.

Deborah Wong: I'll bet that took some saving.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, it must have been a horrendous burden, because at the time that they bought it, I don't think there were too many of us. It seems to me there were only about four of us, I think. But then the kids came. My mother had eleven, and she lost two. One was a stillbirth, and the other one. I don't know what happened to it.

John Kanda: Have any of the Japanese you've interviewed talked very much about prejudice in Riverside during the war, or at the start of the war?

Deborah Wong: Very few have actually mentioned specific incidents where something happened. What most of the Nisei talk about was the general feeling of the town and a generalized kind of hostility. Like, towards the end there, the whole downtown area was declared a zone off limits to Japanese Americans, and then there was the curfew.

John Kanda: Yeah, the curfew.

Alice Kanda: We had a curfew, yes. We just didn't put ourselves in a position where we would be harmed or whatever. I mean, we were harm. I know when I used to come home from where I stayed, I just-like I say-I came in the daylight and went home in the daylight. I just didn't even look at people, really.

Deborah Wong: Kept a low profile?

Alice Kanda: Right, right. I thought that was best.

Deborah Wong: I have looked at The Press-Enterprise from those months, and there's some tremendously hostile and racist stuff in there about the war and all that and the local Japanese. Did you all read the newspaper at that time?

Alice Kanda: I think we were getting The Press-Enterprise, yeah.

Deborah Wong: There were some very unpleasant editorials. I should show you photocopies of them to see if you remember.

Alice Kanda: Really? I don't remember. I guess I was so worried about the family, and my dad was gone. What was going to happen to all of us.

Deborah Wong: In the '80s, did your family apply for reparations?

Alice Kanda: We did. They sent us some forms. We were very fortunate in that we weren't made to be active in that type of thing. I mean, people who worked in Washington did all of that, I guess, or the JACL. And so we just got forms. They asked us during what time were we there, and they asked us where our barracks were, and what did we do, and so on. [ pause ] But they shoulda done that sooner, when the Isseis were still living, so many of them, because they're the ones that really. they're the ones that lost. I mean, most of us were teenagers, so we didn't have the loss, but that's the way I felt about the reparations.

Deborah Wong: That it should have happened sooner.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, right. But camp . They were supposed to be protecting us, but here was this machine gun aimed at us , you know. [ laughed ] That I didn't understand.

Deborah Wong: The job you got was as a nurses' aid?

Alice Kanda: Yeah. I had an opportunity to do something and I've always liked nursing, so I thought, well, I'll try it.

Deborah Wong: How long did you work in the clinic or hospital?

Alice Kanda: Gee, I can't remember really. Let's see, we evacuated in '42, and it was only a couple of months. I guess I worked there almost a year.

Deborah Wong: Before you got sick.

Alice Kanda: Mm-hm, right. I had TB and the neighborhood knew I had TB and they wouldn't even walk in front of the barrack. They used to go clear around. So I was glad I was able to go to another area. That they didn't make me stay where I worked.

Deborah Wong: So you all came back to Riverside in 1945 and opened up the store again, I guess?

Alice Kanda: Yeah. Opened up the store, and one of the men that my dad used to work for came and he brought us some furniture, so that helped. And then he helped us financially, too.

Deborah Wong: Really? Was this another Japanese.?

Alice Kanda: No, he was a Caucasian man. He was a Canadian. So there were nice people. I went to business college. I worked in San Bernardino and went to business college. Not immediately, but after the family was more or less settled.

Deborah Wong: And by '48, you were in Los Angeles .?

Alice Kanda: Right.

Deborah Wong: So you were only back in Riverside for a few years.

Alice Kanda: A few years. I worked at the telephone company for almost thirty-five years. I was in management for about twenty-five, I think.

Deborah Wong: So you moved right up.

Alice Kanda: No, it took me awhile, but yeah.

Deborah Wong: You're probably getting tired at this point, but one last question: where are your parents buried?

Alice Kanda: In Riverside . My mother and dad are buried in Crestlawn-that's toward Sierra. What's that called? It's toward Arlington way. My sister isn't buried there, though. She's buried off of Central.

Deborah Wong: In Olivewood.

Alice Kanda: Yes. In the newer section.

Deborah Wong: I have gone around Olivewood cemetery and Evergreen looking for Asian headstones. There are a lot of Chinese and Japanese in Olivewood, mostly from earlier-the 1910s, the 1920s.

Alice Kanda: Yeah, there was a quarter for the Chinese, when I was growing up. We had a Chinatown . The Chinatown 's no longer there, no. It was on Brockton .

Deborah Wong: So you remember it. Did you ever go there and walk around?

Alice Kanda: No, but I knew it was there, my folks used to. Oh, I did go down there, because on the outskirts they sold potato chips and I used to pick it up at the store, that's right. I just knew the Kim sisters, that's all-they were Chinese sisters. And I don't even know how I met them, but years ago, when I was still working, I used to go window shopping in Pasadena, and there was a little hamburger place and I used to sit there and have lunch, and one day I sat next to them and they looked at me and I looked at them and they said, "Aren't you from Riverside?" It was the strangest thing! And I said, "Yes!" And I said, "You're the Kim sisters!" They said, "Yes!" [ laughed ] After all these years! I don't even know if they're still-they were a lot older than I was, so I don't even know if they're there.

Deborah Wong: You're probably anxious about your rice and corn at this point, so I should let you check!

Alice Kanda: We can have dinner, too, and then we can talk later.